Metaphysics, Part 2: Hunks, Lumps, Statues, and WandaVision

Puzzles in object theory and WandaVision's metaphysical moment.

One common question about philosophy goes something like, “What exactly do philosophers do?” It’s an understandable question, because whatever is going on when “doing philosophy” isn’t immediately clear or obvious to the average observer. Philosophers do a lot of things, but I like to say that one of the things philosophers do well is examine more closely many of the assumptions and concepts that are typically taken for granted in most other contexts. In the field of metaphysics, a good percentage of metaphysicians focus on a sub-field called object theory, which can roughly be described as examining what counts as an object and why.

(Note: in this post I will only be considering things that are thought to be physical or concrete objects. Following Dan Korman and others, I reserve the term “object” for concrete objects and the term “entity” as a general term for things that are either concrete, abstract, or spiritual. The metaphysical status of abstract entities is one of my favorite topics, but deserves a post on its own down the line.)

I’ll give a broad overview of some issues metaphysicians think about when trying to pin down the slippery relation of constitution, before moving on to the relation of composition in the next post.

Constitution

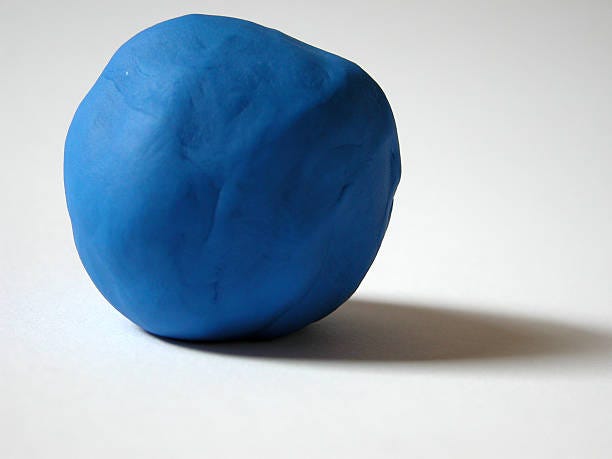

Some philosophers talk about an object being constituted by material. This desk in front of me is constituted by wood, for example. In that case there is a relation of constitution between the wood on the one hand, and the desk on the other. But when we talk in this way, as if there are two objects (the wood and the desk) we get all kinds of questions and puzzles: is this particular wood identical with the desk? It doesn’t seem so, because you might think I can replace one of the legs of the desk with a different wooden leg, so that the wood changes but the desk retains its identity (or does it?). Alan Gibbard’s classic 1975 piece, “Contingent Identity” discusses this issue and is one of the most well-known papers on the topic. Gibbard considers whether a clay statue he calls “Goliath” is identical to the lump of clay he calls “Lumpl” that makes up the statue. On the one hand, it looks like they are identical, because Goliath and Lumpl are co-located and have all the same physical characteristics. On the other hand, if you smash Goliath into a misshapen piece of clay, Goliath ceases to exist while Lumpl is still there in all its lumpyness. So it looks like they are not identical, and we actually have two objects. But if you weigh Goliath, then weigh Lumpl, and add their weight together, then the weight of the physical object in front of you is doubled. That doesn’t seem right. So there are ongoing discussions in the literature on object theory that try and sort through how we make sense of constitution.

There is a nice paper by Michael Rea from 1995 called “The Problem of Material Constitution”,1 where he highlights many of these kinds of puzzles of object theory, and attempts to unite these problems into a more fundamental, underlying problem. Rea’s paper gives helpful summaries of classic metaphysical puzzles while identifying a cluster of assumptions that are needed for these puzzles, such as an Existence Assumption (a bunch of parts can compose a whole), an Identity Assumption (a bunch of parts are identical to a whole), etc.

Rea’s paper includes the Ship of Theseus puzzle; you may remember the heads of metaphysicians everywhere exploding when the Ship of Theseus puzzle came up on the Marvel show, WandaVision:

The episode prompted a surge of online interest in the metaphysical puzzle, including an explainer in Men’s Health. (My favorite line: “I have a degree in philosophy—and I say that very hesitantly, knowing how annoying it is for anyone with a philosophy degree to tell you they have a philosophy degree; mostly, we should just shut up.” I don’t disagree.)

But for reasons I’ll only briefly mention here, I don’t think the relation of constitution is that clear for explaining and describing objects. I think Brian Leftow is on to something when he describes his view of constitution this way (he calls his view “deflationary”) in his recent article, “The Trinity is Still Unconstitutional”:

My story about Hunk [the equivalent of Lumpl] and Athena [the equivalent of Goliath] goes this way. Hunk is mind-independent. There are hunks of matter, and would be were there no finite minds at all. Their parts compose them in convention-independent ways. There are hunks only where ordinary pre-philosophical thought sees real objects…Athena is an artefact. Artefacts are mind-dependent. They are what they are due entirely to their makers’ actions and intentions. If a sculptor scrapes a line in a rock, meaning to make a sculpture (titled ‘Marked Rock’), that makes it a sculpture. It is one simply because the sculptor meant it to be. If I marked a rock the same way, not meaning to produce art, it would not be a sculpture. Doric columns are not statues. The sole reason is that they were not meant to be. Had someone carved what looks like a Doric column and meant it to be a statue, it would be a statue. Statues, like artefacts generally, are conventional objects. To be a statue is just to satisfy the conventions for being a statue. Our conventions require inter alia that someone meant the statue to be a statue. Had a bolt of lightning blasted Athena into shape, she might look like a statue, but she would not be. Any conventional object is mind-dependent, since conventions cannot exist without minds to make them and exist only as long as minds observe them.

As I see it, the sculptor shaped Hunk. This produced a shaped hunk of clay. The shaped hunk is a statue because it falls under the statue convention: Athena’s coming to exist depends on a convention. Athena’s persistence also involves convention. As long as there is a hunk in the right place whose shape is close enough to Athena’s original shape, our concepts say that Athena persists – and the standards for ‘close enough’ are up to us. That’s it. (p. 9)

Two takeaways I want to point out: first, Leftow’s account here, and the article as a whole, illustrates at least one way in which these weird, abstract issues within object theory can relate to important issues in theology. William Hasker believes the one God constitutes the three Persons, and Leftow makes a good case against it. But to do so takes at least some knowledge of the issues within object theory that involve constitution. So in some contexts it’s worth being informed about metaphysical issues within object theory—beyond language about essence, substance, and properties—to address some of the claims out there that pull from the vast, full suite of metaphysical concepts.

Second, Leftow’s claim that “There are hunks of matter, and would be were there no finite minds at all” is actually a controversial claim within metaphysics.2 To see why, in the next post I’ll say a few things about a relation that differs in many ways from the constitution relation, and one I far prefer: the relation of composition. To show my hand a bit, I think it is not at all obvious that there are hunks of matter apart from social conventions and, therefore, minds. If we assume for the sake of simplicity that the universe is made of fundamental atom-like things that cannot be further divided, then 1) it isn’t clear what the conditions are for what counts as a hunk of matter and what doesn’t, and 2) it isn’t clear whether one hunk of matter differs from the many atoms that make up the hunk. I’ll get into that issue in particular in the next post.

Looking at this paper again, I notice there may be some conflation of the constitution relation and the composition relation. But even if that’s true, the main thesis is still helpful, and the conflation can be somewhat forgiven since it was written before much of the recent work on composition and mereology (stay tuned for the next post).

Leftow is well aware of this. I’m just scrutinizing his point to illustrate the topic for next time.